Lieut.-Col. Henry Harpur Greer and family arrived in Tauranga on 10 March 1864 and made their home at ‘High Trees,’ one of Tauranga’s earliest European homes. He was in command of the 68th Regiment during the Battle of Gate Pā | Pukehinahina on 29 April 1864, and seven weeks later was commander of the entire British force at the Battle of Te Ranga on 21 June 1864 when 151 Māori were killed, wounded or captured. Story researched, written and published by Debbie McCauley as part of her research paper Identity and the Battle of Gate Pā at Pukehinahina (29 April 1864). Updated with input from Henry’s second great grandson, Mike Dottridge.

Henry Harpur Greer was born on 24 February 1821 at ‘The Grange’ at The Moy (Irish: an Maigh, meaning ‘the plain’), a large village in County Tyrone, Northern Ireland.

Henry’s parents were Joseph Henry Greer and Mary Greer (née Harpur) who married in County Tyrone on 5 June 1816. Henry was the third of six siblings; Emily (c. 1818), Jane (1820), Henry (1821), Anna (1827), Thomas (1828), and Maria (1846).

Oil painting of Henry Harpur Greer. Digital image donated to Tauranga City Libraries in 2003 by Mike Dottridge (second great grandson of Lieut.-Col. Henry Harpur Greer). Original measures 210 x 150 mms. Tauranga City Libraries Image 03-143.

Joseph Henry Greer (known as ‘Orange Joe’ / spelt ‘Grier’ in British Parliamentary records) is said to have been an artillery officer, and was one of twelve Deputy-Lieut.’s of County Tyrone in Northern Ireland, which is still part of the United Kingdom. He was also a Justice of the Peace and, more relevantly, Grand Master of the Orange Order in County Tyrone. The Orange Order was an association representing Protestant sectarian interests, even though, as Deputy-Lieut., he was not supposed to be partisan. In fact he was criticised in a House of Lords inquiry in the 1830s! This sort of background and experience – of discriminating against indigenous Catholics in Ireland – was shared by countless Northern Irishmen around the British Empire.

Henry was educated at Royal School, Dungannon, County Tyrone, Ireland. He joined the 68th (Durham) Light Infantry (‘The Faithful Durhams’) as an Ensign on 10 September 1841. His promotions were;

- 1841 (10 September): 21-year-old ensign,

- 1844 (20 August): Lieut.,

- 1847 (31 December): Capt.,

- 1854 (29 December): Maj.,

- 1859 (18 February): Lieut.-Col.,

- 1864 (18 February): Brevet-Col.,

- 1869: Major General,

- 1881: Honorary Lieut.-Gen. (Well Done the 68th, p. 218).

Henry and Agnes Isabella Knox married on 14 February 1850 at Lorrhar Church in County Cavan, Ireland. Agnes was the daughter of Venerable Edmund Dalrymple Hesketh Knox and Agnes Mary Knox (née Hay). Their marriage notice appeared in the Clonfeacle Parish Marriage Announcements, 1832-69;

GREER-KNOX. February 14th, at Lorrha Church, by the Rev. Marcus McCausland, HENRY HARPUR GREER, Captain, 68th Light Infantry, eldest son of JOSEPH HENRY HARPUR GREER, The Grange, county Tyrone, to AGNES ISABELLA, youngest daughter of the VEN. THE ARCHDEACON OF KILLALOE, and granddaughter of the late HON. THE LORD BISHOP OF LIMERICK.

Clonfeacle Parish Marriage Announcements, 1832-69 (22 February 1850).

The children of Henry Harpur Greer and Agnes Isabella Greer (née Knox)

- Greer, Joseph Henry (1855-1934) Joseph Henry, generally known as ‘Harry’ and sometimes as Henry (even when he was knighted in the 1920s and became ‘Sir Henry’) but never as ‘Joseph’ [his daughter Emily Charlotte reported that her grandfather, Joe, had erupted at the boy’s baptism and insisted he be named Joseph, when the parents were intending to call him Henry] was born in Ireland on 9 February 1855. He was educated at Wellington College, Wellington, Berkshire, England and at Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst, Berkshire, England, marrying Olivia Mary Beresford on 9 December 1886. Henry gained the rank of Captain in the service of the Highland Light Infantry. As an army Captain he was based in Singapore until his father’s death in 1886, but, perhaps more relevantly, he inherited a large sum of money from his mother’s sister in 1886 (the same year that his father died) and swiftly left the army to become a racehorse breeder, moving from County Tyrone to The Curragh, in County Kildare, nearer to Dublin (Ireland). After Ireland’s independence he was a Senator in the upper house of the Dail – one of the representatives of the Protestant Anglo-Irish minority (the former ruling class in Ireland) for two parliamentary sessions. He was invested as a Knight Commander, Royal Victorian Order (K.C.V.O.) in 1925. Henry died, aged 79, on 24 August 1934.

- Greer, Agnes Mary (1858-1934) Agnes was born on 11 September 1858 at Rangoon in Bengal, India. She didn’t marry and was aged 28 when her father died. Agnes died on 17 May 1934 at ‘The Grange’ in Tyrone .

- Tupper, Emily Charlotte (née Greer) (c. 1863-1929) Emily married Reginald Geoffrey Otway Tupper (1859-1945) on 30 April 1888 at St Marks, St John’s Wood in London. She died on 15 February 1929 at Whitehill Grange in Bordon, Hampshire. Before her death Emily wrote a memoir, a portion of which can be found in Appendix 1.

- Greer, Isabella Knox (1865-1865) Born prematurely at Tauranga on 23 March 1865 after a horse bolted while her mother was riding. Isabella died a few weeks later, in June 1865. Tauranga’s Mission Cemetery records show that she is buried there (Index No. 85, p. 6).

Henry and Agnes were initially based in Ireland before moving to Malta. Henry would spend his military career with the 68th Regiment, eventually rising through the ranks to become a commanding officer.

During the Crimean War (1853-1856), Greer avoided most of the fighting (and his portrait as a General consequently does not include any relevant Crimean battle medals), as he was managing supplies, based in Malta for most of the time. In 1855 Agnes was back in Ireland for the birth of her eldest child, Harry. Henry’s daughter Emily Charlotte recorded that her mother and the baby then travelled to Zante in the Ionian islands (Greece), after the end of operations in Crimea and before the regiment departed for Burma at the end of 1857.

A year earlier, on 5 November 1856, Henry had been involved in an accident;

…a youth called Camliche, whose father, a fine old gentleman, owned an estate in the N. of Corfu, shot Colonel Greer of the 68th all over the face. His eyes luckily escaped.

Well Done the 68th (p. 119).

After a spell in Burma while her eldest child, Harry, remained in Ireland, Henry’s wife Agnes fell ill and returned home. Her husband followed her while the rest of the 68th remained in Rangoon. Henry had been in command of the 68th in Rangoon at the end of the 1850s (1858-1863) where they provided soldiers to guard the Mughal royal family (exiled to Burma following the insurrection in India that the British still call the ‘Indian Mutiny’).

Emily Charlotte recorded that the family lived in the early 1860s first in Portsmouth and then in Dublin (possibly going there when Henry Harpur’s father, Joe, died in 1862). They were consequently in Portsmouth or Dublin when the order arrived to travel to New Zealand.

In December 1863 Henry, along with with his wife Agnes and three of their children, sailed from England on board the Silver Eagle. They arrived in Auckland on 3 March 1864:

The magnificent clipper ‘Silver Eagle,’ Captain W. H. Longman, arrived from London, on the 3rd instant. She sailed from Torbay on the 12th December, was two days at Pernambuco, not withstanding which nessary deviation, she has made the unexampled passage of eight-two days… The ‘Silver Eagle’ has brought, in heath and safety, an addition to General Cameron’s forces of between 340 and 350 officers and men under command of Colonel Greer, 68th Regiment, comprising drafts fo the 12th, 43rd, 68th Regiments and Army Hospital Corps. These will not only be welcome but most opportune augmentations as well as in men, as in officers, to their respective corps.

New Zealand Herald (5 March 1864, p. 4).

In early January 1864 the 68th (Durham) Light Infantry (‘The Faithful Durhams’) arrived in New Zealand from Burma. They reached Tauranga on board the HMS Miranda under Colonel Meurant on 22 January 1864. The 68th built a defensive earthwork at Te Papa known as the Durham Redoubt. The site would be built over in the 1870s to raise the level of Hamilton Street. The redoubt was situated on the modern day area bounded by Durham Street, Hamilton Street, Cameron Road and Harington Street.

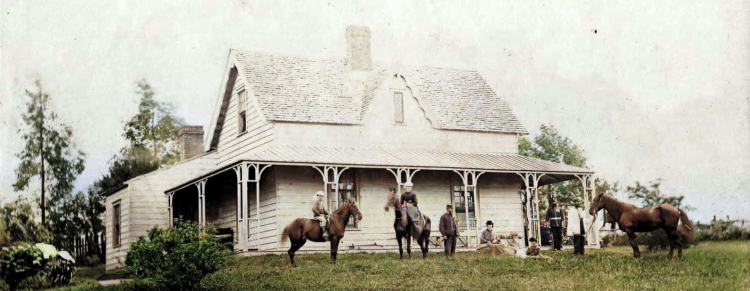

The Greer family arrived in Tauranga on 10 March 1864. They made their home in one of Tauranga’s earliest European homes ‘High Trees.’ The house was close to Durham Redoubt. It was originally built near the Mission Institute by Rev’s Charles Baker (1803-1875) and Edward Blomfield Clarke (1831-1900), who were in charge of the educational establishment. It was completed by the end of 1860. In early 1864 Col. George Carey occupied ‘High Trees’ followed by Lieut.-Col. Henry Harpur Greer (1821-1886) from March 1864 and then Ebenezer. ‘High Trees’ seems to have been demolished in 1933 and flats built by businessman E. T. Baker. During the 1970s the flats were demolished to make way for the car park of the Commercial Traveller’s Club, which was later demolished for the Kingsview high rise apartment complex (Central Tauranga Heritage Study, p. 42).

Lieut.-Gen. Greer commanded the full 68th Regiment of 700 men during the Battle of Gate Pā | Pukehinahina. His Report on the Battle of Gate Pa to the Deputy Adjutant General from Camp Puke Wharangi, dated 1st May, 1864 can be found in Appendix 2.

Henry was commander of the entire British force at the Battle of Te Ranga on 21 June 1864 when 151 Māori were killed, wounded or captured. Before and after the battle he took time to hastily scribble notes to his wife Agnes which can be found in Appendix 3.

As a result of Te Ranga, Henry was made a Companion of the Order of the Bath (C.B.). His report on the Battle of Te Ranga; Colonel Greer to the Deputy Quarter-Master-General, Camp Te Papa; Tauranga, 21st June, 1864, can be in Appendix 4. This is despite stories about how he treated those he was in charge of, being described as;

…a brutal disciplinarian who frequently flogged his troops at public displays on today’s Wharepai Domain.

Buddy Mikaere (3 July 2019).

Henry made another report to the Military Secretary; Camp, Te Papa, Tauranga, 27th June, 1864, which can be found at in Appendix 5. It was in the grounds of the Greer family home ‘High Trees’ that the ‘surrender of arms’ by Māori took place on 25 July 1864.

Henry’s wife Agnes and their daughter Agnes Mary both suffered from typhoid fever while living in Tauranga. The whole family did a good deal of horse riding around Tauranga, Agnes even having a horse bolt whilst she was riding. The effects of this were to be severe, as a week later, on 23 March 1865, Agnes went into labour prematurely with their fourth child, Isabella Knox Greer, who died a few weeks later. Captain Charles Shuttleworth, an officer with the 68th Regiment, recorded the sad events in his diary;

- 23 March: Mrs. Greer still very ill and in fact does not improve and I think the case is serious.

- 24 March: Mrs. Greer prematurely confined last night and very dangerously ill this afternoon.

- 11 April: Mrs. Greer getting better and Greer quite changed – does not care about these reports of natives breaking out again.

- 15 April: Band played first time since Mrs G. illness.

- 17 April: Greer not out himself – said he was ill.

- 26 April: Mrs. H. Greer had Trent up to orderly room in my presence and pitched in to him for putting officers under arrest for trivial things and spoke well on the subject.

- 13 June: Greer and Mrs. went off today to Auckland per steamer “Egmont”.

- 24 June: Greer returned from Auckland by steamer.

- 8 July: Greer went to Auckland.

- 24 July: Steamer came in this morning with Greer, Mrs. G and Miss Goring. Mrs. G. much better (Well Done the 68th, pp. 163-165).

In 1866 the Greer family returned home. They firstly lived in a hut at Aldershot. In 1869 Henry retired from the 68th to command a Depot in Ireland, finally retiring from the Army in 1881 with the rank of Honorary Lieut.-Gen. He served as a Deputy-Lieut. for Tyrone.

Henry died, aged 65, on 27 March 1886 at the family home, ‘The Grange’, at The Moy in County Tyrone, Ireland. His death was reported in the Bay of Plenty Times:

The death has been reported from the county Tyrone of Lieut.-General H. H. Greer, C.B., formerly commanding the 68th Regiment. He took a leading part in the New Zealand war of 1864-6. General Greer was son to a well known Tyrone man ‘Joe Greer’ commonly known as “Orange Joe” who held the office of Grand Master of the county Tyrone Orangemen for many years up to the time of his death and was succeeded by Captain Mervyn Stewart who held that office up to the year of his departure for New Zealand.

Bay of Plenty Times (1 June 1886, p. 3).

The suburb of Greerton situated next to the suburb of Gate Pā in Tauranga is named after Henry, as is Greerton Road. In 1979 the servant’s quarters and washhouse that stood behind ‘High Trees’ was moved to the Tauranga Historic Village where it has been given the misnomer ‘Colonel Greer’s Cottage.’

Agnes died on 4 August 1912. According to her daughter, Agnes had an excellent singing voice and was not at all bigoted (whereas Col. Greer’s father, Joe Greer, was considered by Agnes to be a ‘bigot’).

Appendix 1: Memoirs of Emily Charlotte Tupper (née Greer) [courtesy of Mike Dottridge]

My father had now commanded the regiment since the Burma days, and when the regiment embarked for New. [sic] Zealand in a sailing ship, my mother with her three children, and a large proportion of the wives and families of the officers and men, also went out as a matter of course. It took 84 days to sail out, round Cape Horn, and the smallness and discomfort of the ship, must have been extreme; but my mother took it all in the day’s work. They were about three years in New Zealand, and my mother spent most of the time at Tauranga in the North Island.

When they first went out, they had a great deal of kindness from Bishop Selwyn, and his wife. He was the first Bishop of Melanesia, and was a man of immense Christianity and humour, which do not always go together. He loved his flock, hut found the cannibal propensities a little trying. My father used to tell a story of his about a native chief, who had two wives, and refused to give them up, after he had become a Christian. One day however, he arrived with a tearing race, and said, “Fxo very good Christian now, have only one wife.” So the bishop asked what he had done with the other one, to which the chief replied with a broad grin, “I ate her”.

My father commanded a brigade during the time they were there as he was the senior colonel in those parts, and during part of the time a Naval brigade, commanded by Commander the Hon. Edmund Freemantle was under his orders. Captain Freemantle was amazingly plucky, not to say foolhardy, and risked his life in a way that disturbed my father, who felt responsible for him. Another Naval man who served under him was a midshipman Charles Hotham, now Admiral Sir C. Hotham; and for his gallantry my father recommended him for promotion and he was made lieutenant straight away; which was most unusual, and caused Admiral Hotham to go up the list and get to the top of his profession at an abnormally early age.

My father was in command at the battle of the Gate Pah, and also in another successful engagement, and he was rewarded by the C.B. The Maoris and he became great friends, after they had been beaten. They came to his house at Tauranga, and laid down their arms on the lawn in front of the house; arid from among them he brought home a large collection of Maori weapons, which are now at my brother’s house.** One of the officers of the 68th painted a picture of the scene, of the natives laying down their arms, and we had it at home. I think it was amazing that my mother lived there close to the fighting line, in complete comfort and security. She never thought of feeling nervous, so complete was her confidence in my father and the 68th. She and my sister Agnes both had typhoid fever very badly while out there, and nearly died; and another little daughter was born out there, and only lived three weeks.

We all returned home in 1866, when I was three years old, my brother Harry being eleven, and Agnes eight. They both, and my parents rode a great deal out there, (my mother was run away with a week before the little sister was born) and the only dim recollection I had as a child of my life out there, was of falling out of a box saddle, and being caught by someone, probably a soldier. I used to be nursed and played with a great deal by the men; my proper nurse being the wife of a sergeant. She and her husband settled down in New Zealand after he left the regiment, and she was still living there in 1900. My parent’s [sic] greatest friend in the regiment was the adjutant Charles Covey, who seems to have had a very bad love affair with the beautiful wife of a planter. I don’t remember him at all, but he lived until I was in my teens, and he had two maiden sisters who were very devoted to my mother…

Whe[n] the 68th ultimately came home (also in a sailing ship, but this time round the Cape of Good Hope) they went first to Aldershot where we lived in a hut, and I have a faint recollection of a long passage with all the doors opening off it.

Note from Mike Dottridge: ** “my brother” refers to Harry Greer, who, at the time of writing in the 1920s, was living in a large mansion (called ‘Curragh Grange’) in Newbridge, Country Kildare, Ireland. This statement, that the weapons were still in her brother’s house, was contradicted by an assertion in a memoir written by Emily’s daughter, Loveday Paton (née Tupper), who lived for six months with Harry’s family in 1921, and who noted that he had got rid of the weapons, fearing that there was a curse on them (after both his sons were killed in 1917).

Appendix 2: Colonel Greer’s Report to the Deputy Adjutant General from Camp Puke Wharangi, dated 1st May, 1864.

Sir, I have the honour to state for the information of the Lieut.General Commanding that in compliance with his instructions I marched out of Camp with the 68th Light Infantry, carrying one day’s cooked rations, and a greatcoat each, on the 28th instant, at a quarter to 7 o’clock p.m., my object being to get in rear of the enemy’s position by means of a flank march round their right. To accomplish this it was necessary to cross a mud flat at the head of a bay about three-quarters of a mile long, only passable at low water, and then nearly knee deep, and within musketry range of the shore, in possession of the enemy – rough high ground, covered with ti-tree and fern.

At the point at which I got off the mud flat there is a swamp about 100 yards broad, covered with ti-tree about 5ft. high, on the opposite side of which the end of a spur – which runs down from high ground in rear of the pa – rises abruptly. This was also covered with heavy fern and ti-tree. It being of the first importance that these movements should be accomplished without attracting the attention of the enemy, my instructions were to gain the top of the spur alluded to during the darkness, and to remain there until there should be sufficient light to move on.

The regiment was all across, lying down in line across the crest of the ridge, with picquets posted around them, at 10 o’clock, which was two hours before the moon rose. I beg here to state that to the well-timed feint attack made by the Lieut-General Commanding on the front of the enemy’s pa, I consider myself indebted for having been enabled to accomplish this, the most difficult part of the march, without being attacked at a great disadvantage, and exposing the movement to the enemy; for when we reached the top of the ridge, the remains of their picquet fires were discovered, the picquets having no doubt retired to assist in the defence of the pa.

About half-past 1 a.m. I advanced, and at 3 o’clock I reached a position about 1000 yards directly in rear of the pa. I was guided in selecting this position by hearing the Maoris talking in their pa, and the sentries challenging in our headquarters camp. It was dark and raining at the time. I immediately sent Major Shuttleworth forward with three companies to take a position on the left rear of the pa, and I placed picquets round the remainder of the rear, about 700 yards distant from it.

At daybreak I despatched three companies to the right under command of Major Kirby and posted a chain of sentries so that no one could come out of the pa without being seen. Up to this time the enemy did not appear to be aware that they were surrounded; they were singing and making speeches in the pa. Later in the morning Lieutenant-Colonel Campbell, C.B., Deputy Quarter-Master General, visited my post, having an escort with him of thirty men of the Naval Brigade under Lieut. Hotham, R.N., and seeing that I wanted a reinforcement on my right, he left his escort with me, and I received valuable assistance from that excellent officer and his party. About the same time Major Shuttleworth moved more to his left and closer to the pa.

These positions were not altered during the bombardment, except temporarily, when the Maoris showed a disposition to come out at one or other flank, or when it was necessary to move a little from a position getting more than its share of the splinters of shell which kept falling about all day during the bombardment. When the bombardment ceased, and the signal of a rocket let me know that the assault was about being made, I moved up close round the rear of the pa in such a position that the Maoris could not come out without being met by a strong force.

About 5 o’clock p.m. the Maoris made a determined rush from the right rear of their pa. I met them with three companies, and after a skirmish, drove the main body back into the pa; about twenty got past my right, but they received a flank fire from Lieut. Cox’s party (68th 60 men) and Lieut. Hotham’s (30 men) Naval Brigade, and sixteen of the Maoris were seen to fall; a number of men pursued the remainder. By the time I had collected the men again and posted them it was very dark. My force available on the right was quite inadequate to cover the ground in such a manner as to prevent the Maoris escaping during the night; in fact I consider that on such a wet dark night as that was nothing but a close chain of sentries strongly supported round the whole rear and flanks could have kept the Maoris in, and to do that a much stronger force than I had would have been necessary.

During the night the Maoris made their escape. I think that, taking advantage of the darkness, they crept away in small parties; for during the night every post saw or heard some of them escaping and fired volleys at them. The Maoris, careful not to expose themselves, never returned a shot during the night, but there were occasional shots fired from the pa, no doubt to deceive us as to their having left it.

I cannot speak too highly of the conduct of the 68th during the march on Thursday night; it was performed with the most complete silence and regularity. I have also the greatest pleasure in being able to state that during the whole of their fatiguing duty they were always ready to obey cheerfully any order they received, and after dark it was most difficult to move about from the way in which the ground in the rear was swept by the musketry in front.

I am much indebted to the officers and non-commissioned officers for the active intelligence and zeal with which they performed their duty. I beg to mention particularly Major Shuttleworth, 68th Light Infantry, who, with the guide and six men, went feeling the way to the front during the night march, and afterwards commanded on the left, repelling several attempts of the Maoris to get away in that direction.

Captain Trent, 68th Light Infantry, who with his company formed the advance guard during the night march, and performed that duty with much intelligence, and was afterwards engaged on the left, where he enfiladed a rifle pit, and in the front covering a working party.

Lieut. Cox, 68th, who occupied with judgment and good effect an important position on my right, where he enfiladed a rifle pit, and quite shut up what appeared the principal point of egress from the pit. Lieut. Hotham, Royal Navy, who was with a party of the Naval Brigade at the same post with Lieut. Cox.

To Lieut. and Adjutant Covey, 68th Light Infantry, Field Adjutant, I am on this occasion, as on every other where duty is concerned, much indebted for the zeal and intelligence with which he has assisted me in seeing my orders carried out. During the whole time he was constantly on the alert, and active wherever he was required. To all I owe my best thanks.

I wish to bring to particular notice the admirable manner in which the regiment was guided by Mr Purvis, who volunteered to act as guide on the occasion. He went to the front with Major Shutteleworth and six men, and without hesitating or making a mistake, brought him straight to the position I was to occupy.

The whole of the 68th Regiment was back in camp at 4 p.m. yesterday. The Casualties are as follows:- Killed – Sergeant, 68th Light Infantry. Wounded – 16 Privates Infantry. I have, etc., H. H. GREER, Col. and Lieut.-Col. 68th L.I., Commanding Field Force, Camp Puke Wharangi.

Appendix 3: Colonel Greer’s notes from the Te Ranga battlefield

In January 2015 Mike Dottridge, a descendant of Henry Harpur Greer, donated Greer’s original notes to his wife Agnes to Tauranga City Libraries. The notes were written in 1864 from the Te Ranga battlefield. Transcribed by Stephanie Smith in 2015.

Before the battle at Te Ranga on 21 June 1864, Colonel Henry Harpur Greer took the time to scrawl a quick note to his wife Agnes. On a ‘cash account’ page torn out of a small diary, he wrote – hastily and in pencil – ‘Dear Agnes we have / got a lot of Maoris / out here in pah & Im [sic] / hammering away / at them, I hope we / shall get them out / before night, I have / sent in for[?] more / guns. don’t be the / least alarmed. / yrs HHGreer / God bless us.’

And when the battle was over and he had survived, he wrote Angus another note, on another page from the diary. ‘Dear Agnes we / have taken the / pah & killed heaps of / Maoris, our men / are in hot pursuit / not many of our / people hit / yrs HHG / Thank God’.

For the rest of her life Agnes Greer treasured these notes in a tiny envelope, which she marked ‘My own beloved Henry’s / notes, during the engagement / of Te Ranga he wrote them / 21st. of June 1864.’ They were retained in the family. In January 2015 Mike Dottridge, Greer’s descendant, generously donated the original notes and the envelope to Tauranga City Libraries, where they are stored in the fireproof archives room.

This is not the first time that Mike Dottridge has generously donated items to Tauranga City Libraries as reported in City Views – News from the Tauranga District Council on 3 April 2003 (Issue 5): Colonel Harpur Greer, Commander of the British troops based in Tauranga in 1864 A little bit of Greerton’s past came home recently. The great, great grandson of Colonel Henry Harpur Greer made the journey here from England to return some historic items to their “proper” place and to research his family. While it may be more common for New Zealanders to head to Britain for family research, Mike Dottridge and wife Jane combined a fact finding trip with a visit to their son in Wellington. The couple visited Tauranga Library’s New Zealand Room to discover more about his great, great-grandfather after whom Greerton was named. Colonel Greer came to New Zealand in 1864 as commander of the 68th Durham Light Infantry. He led the division in the Battle of Gate Pa in which the British were resoundingly defeated. A few months later Colonel Greer was again in charge at the bloody battle at Te Ranga, a few kilometres inland from Gate Pa. This time the Maori resistance led by Rawiri was crushed. Colonel Greer went back to Britain a Lieutenant-General. He died in 1886. Mr Dottridge has worked for many years with human rights agencies in Britain. His work focused on the rights of indigenous peoples so, he said, it was quite a shock to find out his great-grandfather played an important role in the colonisation of this area. When Mr Dottridge’s father died four years ago, he discovered various items that had been stored in family memento boxes for many years. Among the treasures were newspaper clippings and photographs. Also in the family were artworks Colonel Greer had brought back from New Zealand. Mr Dottridge believed the items should be returned to this country. He has given Tauranga Library the first photograph of Colonel Greer seen by staff and says it is a good way of making sure the records are in good hands. Mr Dottridge has now returned to England (Source: Early New Zealand Photographers and their successors).

Appendix 4: Greer’s report on the Battle of Te Ranga: Colonel Greer to the Deputy Quarter-Master-General, Camp Te Papa; Tauranga, 21st June, 1864.

Sir,—I have the honour to report for the information of the Lieutenant-General Commanding that I marched out of Camp with a force as per margin. (3 Field Officers, 9 Captains, 14 Subalterns, 24 Sergeants, 13 Buglers, 531 Rank and file) this morning at 8 a.m.

I found a large force of Maoris (about 600) entrenching themselves about four miles beyond Pukehinahina. They had made a single line of rifle pits of the usual form across the road in a position exactly similar to Pukehinahina—the commencement of a formidable pa. Having driven in some skirmishers they had thrown out I extended the 43rd and a portion of the 68th in their front and on the flanks as far as practicable, and kept up a sharp fire for about two hours, while I sent back for re-inforcements as per margin (1 gun, 220 men). As soon as they were sufficiently near in order to support I sounded the advance, when the 43rd., 68th. and First Waikato Militia charged and carried the rifle pits in the most dashing manner, under a tremendous fire, but which was for the most part too high.

For a few minutes the Maoris fought desperately when they were utterly routed. Sixty-eight were killed in the rifle pits. The position was a very favourable one for their retreat; otherwise few could have escaped. The advance force pursued them several miles, but could not get well at them owing to the deep ravines with which the country is everywhere intersected. The infantry pursued as long as they could keep the Maoris in sight. All did their duty gallantly.

The 43rd. was under the command of Major Synge (whose horse was shot); the 68th. under Major Shuttleworth, the First Waikato Militia under Captain Moore, and they each led their men well. It is impossible for me in this hurried report to do justice. I will therefore have the pleasure in a subsequent report to bring those to your notice who more particularly distinguished themselves.

I marched the men back to camp this morning. 107 Maoris were found and carried up to the rifle pits, and we have brought in 27 wounded, all severely, and 10 prisoners. Many more must have been killed in the ravines, whom we did not find. I enclose a report which shows that a large number of Chiefs have been killed, including Rawiri. I am happy to say our casualties have been comparatively small. I enclose a report of the killed and wounded.

I must not conclude without remarking on the gallant stand made by the Maoris at the rifle pits; they stood the charge without flinching, and did not retire until forced out at the point of the bayonet. The name of the position which the Maoris occupied is “Te Ranga.” I have thought this of sufficient importance to request Captain Phillimore to take my report up in the “Esk.”I have, etc., H. H. GREER, Colonel Commanding Tauranga District.

Appendix 5: Greer’s report to the Military Secretary: Camp, Te Papa, Tauranga, 27th June, 1864.

Sir, I have the honour to state for the information of the Lieut.General Commanding in New Zealand that I have little to add to the report which I sent in on the 21st inst. relative to the engagement at Te Ranga beyond bringing to his notice those who more particularly distinguished themselves.

About 10.30 o’clock the troops were so disposed in front and on both flanks that retreat without heavy loss seemed impossible for the Maoris. About 12.30 o’clock, having reinforced the skirmishers (with two companies of the 68th) and cautioned the men to reserve their fire (which they did in the most steady manner), the advance was sounded, and the men moved as if on parade. To the dash, determination and steadiness with which the attack was made the success which followed is due.

From the fact that the attack was made in Light Infantry order, and from the Maoris having waited for the charge and made a desperate hand-to-hand resistance, more opportunity was offered of showing individual gallantry than might occur in much more extensive operations; but the attack was so simultaneous, and all did their duty so well, it is difficult to make selections. I beg, however, to bring the following to the favourable notice of the Lieut.-General Commanding.

Major Synge, 43rd Light Infantry, commanding the line of skirmishers, who had his horse shot under him in two places when close to the rifle pits. Major Colville, 43rd Light Infantry, who gallantly led the left of the line of skirmishers into the rifle pits, being one of the first in. Major Shuttleworth, 68th Light Infantry, who commanded the support, consisting of the 68th Light Infantry and the 1st Waikato Militia, and brought them up in the most soldier-like manner, and rushed on the pits at the critical moment.

Captain Trent, Acting Field Officer, 68th Light Infantry, who fell severely wounded when leading two companies of the 68th into the left of the rifle pits, and continued cheering on the men until the pits were taken. Captain Smith, 43rd Light Infantry, who is reported to have been first into the right of the line of rifle pits, and whose gallant conduct was so conspicuous. I have forwarded evidence with a view to his being recommended for the Victoria Cross. He was wounded severely in two places. Captain Casement, 68th Light Infantry, who was severely wounded in two places, in front of his company, when leading them into the rifle pits.

Captain Berners, 43rd Light Infantry, who was also severely wounded when leading in front of his company, close to the rifle pits. Captain Seymour, 68th Light Infantry, who took Captain Trent’s place when that officer fell, and led into the left of the rifle pits in the most gallant manner. Lieutenant Stuart, 68th Light Infantry, who was one of the first into the left line of rifle pits, and had a personal conflict with a Maori armed with an Enfield rifle and bayonet, and by him he was slightly bayonet-wounded, but succeeded in cutting him down with his sword.

Captain the Honorable A. Harris, 43rd Light Infantry, who was detached to the right in command of two companies of the 43rd to enfilade the enemy’s position, and afterward brought the companies at the critical moment to assist in the assault. Captain Moore, who commanded the 1st. Waikato Militia, and led his men up to the rifle pits and shared in the assault. Lieutenant Acting Adjutant Hammick, 43rd Light Infantry, who performed his duty with great coolness and courage under a heavy fire.

Lieut.-Grubb, R.A., whose coolness and excellent practice with the six-pounder Armstrong under his command when under fire during the action and subsequently on the retreating Maoris when they had got beyond the reach of the Infantry, was admirable. Surgeon-Major Best, 68th Light Infantry, principal medical officer, who performed his duty assiduously under fire, paying the greatest attention and care to the wounded. I can say the same of Assistant Surgeons Henry, 43rd; Applin, 68th; and O’Connell, Staff; the former was particularly brought to my notice by Major Synge, commanding the 43rd L.I.

Lieutenant and Adjutant Covey, 68th Light Infantry, FieldAdjutant, and Ensign Palmer, 68th L.I., acting as my Orderly Officer, who performed their duty coolly and gallantly, affording me valuable assistance. Lieutenant Covey having been sent a message by me to Major Shuttleworth, when he was on the point of attack, went with the supports, and was dragged into a rifle pit by a Maori, who thrust a spear through his clothes. Ensign Palmer was struck in the neck by a musket bullet and knocked from his horse insensible when riding beside me; when he recovered and had his wound dressed he performed his duty during the rest of the day.

Sergeant-Major Tudor, 68th L.I., who went in front and distinguished himself in several personal conflicts with the enemy in the rifle pits. Sergeant-Major Daniels, 43rd L.I., and Acting-Sergeant-Major Lilley (70th Regiment) of the 1st Waikato Militia, who also distinguished themselves by their coolness and courage. No. 2918 Sergeant Murray, 68th L.I., whose gallantry and prowess were so distinguished I have thought the matter worthy of being recommended for the Victoria Cross, and have with that view forwarded evidence.

No. 2832 Corporal J. Byrne, V.C., 68th Light Infantry, who, when the order to charge was given, was the first man of his company into the rifle pits. A Maori, whom he transfixed with his bayonet, seized his rifle with one hand, and holding it firm, with the bayonet through him, endeavoured to cut him down with his tomahawk. His life was saved by Sergeant Murray. No. 3641, Private Thomas Smith (severely wounded) and No. 518, Private Daniel Caffery, 68th L.I., both distinguished themselves by their gallant conduct in the field, and their prowess in the rifle pits.

I beg to add that during the engagement several reports were forwarded to me stating that a large body of natives were coming down by the Wairoa to attack the camp at Te Papa at low water, the information having been given by friendly natives. Low water on that day was at half-past three o’clock. I was back in camp about half-past two o’clock and artillery, Mounted Defence Force and reinforcements of infantry were following me. I, however, found that every necessary arrangement had been made by Lieut.Colonel Harington, 1st Waikato Militia, who was in command at the Camp during my absence.

I beg to bring to the notice of the Lieut.-General Commanding the readiness with which Captain Phillimore, H.M.S. “Esk,” and the Senior Naval Officer at this station, and Commander Swan, H.M.S. “Harrier,” responded to my request (which I sent immediately on finding the Maoris) that they would lend all their available force for the protection of the Camp. I have since learned that the report of the natives coming down to take Te Papa was true, but that the result of the affair at Te Ranga disarranged their plans. For nearly an hour previous to the assault I had seen a Maori reinforcement coming down from the woods, yelling and firing their guns, and when the advance was sounded they were not more than 500 yards from the rifle pits.

I beg further to add that while in command here I have only endeavoured to carry out the instructions given me by the Lieut.General Commanding and if I have had any success it is to the foresight of those instructions, and to the good discipline and courage of the troops under my command, it is to be attributed.

On Wednesday morning last (22nd inst.) I sent a strong patrol under Major Colville, 43rd L.I., to bury the dead and fill in the rifle pits. 108 Maoris were buried in the rifle pits which they had themselves dug the morning before. The patrol returned the same afternoon without having seen anything further of the hostile natives, nor have any been since observed in the neighbourhood.

In addition to the number buried in the rifle pits, fifteen of the wounded prisoners have died since they were brought in. I am sending up 8 wounded and 11 unwounded prisoners by the Alexandra, and nine are detained for treatment in the hospital at this station, making a total of 151 Maoris accounted for. Enclosed are lists of the arms captured from the enemy and handed over to the Military Store Department, and returns of the killed and wounded of the Forces under my command.I have, etc., H. H. GREER, Colonel Commanding Tauranga District.

Sources

- Bay of Plenty Times. (1886, June 1). Co. Tyrone News (p. 3).

- Bilcliffe, John. (1995). Well done the 68th: the story of a regiment, told by the men of the 68th Light Infantry, during the Crimea and New Zealand wars, 1854 to 1866. Chippenham, England: Picton Publishing.

- Clonfeacle Parish Marriage Announcements 1832-69.

- Dottridge, Mike. (personal communication, 2015).

- Geni Profile: Henry Harpur Greer.

- Mair, Gilbert. (1926). The Story of Gate Pa, April 29th 1864 [Reprinted by the Bay of Plenty Times Ltd in 1937 & 1964. Reprinted by Tauranga Charitable Trust in 2014].

- McCauley, Debbie. (2011, August 5). Identity and the Battle of Gate Pā (Pukehinahina), 29 April 1864.

- McGregor, G. W. & P. J. (2004). Tauranga Historic Village Museum, Souvenir Book.

- McLean, H. Y. & Willocock, J. (1979). Tauranga Mission Cemetery: Otamataha Pa Cemetery Records.

- Mikaere, Buddy. (2019, July 3). Tauranga street names should reflect city’s history. Bay of Plenty Times.

- New Zealand Herald. (1864, March 5). Monthly Summary (p. 4).

- Tauranga City Council & Environment Bay of Plenty. Central Tauranga Heritage Study (p. 42).

- The Peerage.

© Debbie Joy McCauley (2012, updated 2020) | All Rights Reserved | Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Debbie McCauley and https://debbiemccauleyauthor.wordpress.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

You must be logged in to post a comment.